In Memory Of

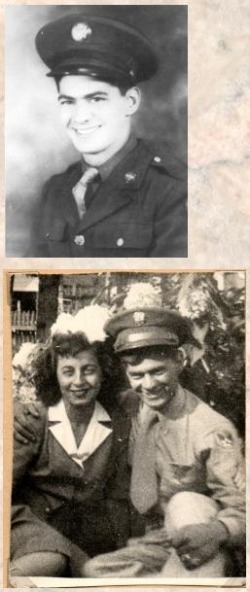

Sgt. Albert N. Spadafora- "Shorty"

Albert and his fiancee, Mary

When I began armorer’s school at Buckley Field, near Denver, Colorado, in January, 1943, occupying the cot next to mine was a short (about five feet, two inches) Italian from Boston whom everyone quite naturally addressed as Shorty. His real name was Albert Spadafora. My first impression of him was somewhat negative—I thought he seemed a little too cocky. That first impression was faulty, however, and before long we became close friends. After completing armorer’s school, we volunteered for aerial gunnery school and subsequently were assigned to the Alfred H. Locke crew. By that time, we were inseparable; where one was, the other was likely to be. Depending on the content, we sometimes shared our letters with each other; and, of course, we always shared the candy, cookies and other treats that we received from home.

Occasionally he asked me to insert a note to his fiancee, Mary.

Shorty and I had promised each other that if anything happened to one of us, the survivor would write the other’s family; so following his death I wrote to Mary, the most difficult letter I’ve ever written. Mary and I still correspond, and I have visited her and Shorty’s family a few times.

Dale VanBlair

Two days [March 8, 1944] later Shorty [Albert Spadafora] flew to Berlin with Lt. Binks, whose gunners were in our hut and whom we knew quite well. When the time came for the planes to return late that afternoon, I went to the hardstand assigned to Binks's plane and waited to greet Shorty, as I had done the other time he had filled in on another crew. He had also met me when I substituted. I saw the 448th formation approach and circle the field and then watched as one plane after another landed and parked, but none pulled into Binks's hardstand. I waited for an hour in hopes that the plane would show up, then began the walk back to our hut. I was very concerned but maintained hope that the plane, for some reason, had parked at another hardstand or perhaps had made an emergency landing at another base, as sometimes happened.

When I returned to the hut, no news was available. The word came a little later: Shorty's plane had ditched in the North Sea and only two of the crew had been picked up by the Air-Sea Rescue. Shorty was not one of them. I was shocked. Not wanting to cry in front of the other men, even though I knew they would understand, I went outside, where it was now dark, went for a walk, and let the tears come. I might as well have remained inside, for when I returned and glanced at the shelf above his cot where the photo of Mary, his fiancee, stood, the tears came again. Several of the men came and sat around me, not saying much, but letting me know that they sympathized.

The two men who were picked up, Sgt. Hood and Sgt. Nugent (I no longer remember their first names) came by our hut after being released from the hospital a few days later and told me what happened. With fuel tanks punctured by flak, they had insufficient gas to make England. As Lt. Binks attempted to ditch, a large wave caught the nose of the plane, which broke in half at the bomb bays. The back half, where Shorty was, sank immediately. Binks, Hood, and Nugent escaped from the front half. The latter two saw Binks struggling in the water not far away, but he went under before they could reach him. Hood and Nugent were picked up by Air-Sea Rescue. Neither flew again, and they were returned to the U.S.

-“Three Years in the Army Air Forces” by Dale R. VanBlair

Occasionally he asked me to insert a note to his fiancee, Mary.

Shorty and I had promised each other that if anything happened to one of us, the survivor would write the other’s family; so following his death I wrote to Mary, the most difficult letter I’ve ever written. Mary and I still correspond, and I have visited her and Shorty’s family a few times.

Dale VanBlair

Two days [March 8, 1944] later Shorty [Albert Spadafora] flew to Berlin with Lt. Binks, whose gunners were in our hut and whom we knew quite well. When the time came for the planes to return late that afternoon, I went to the hardstand assigned to Binks's plane and waited to greet Shorty, as I had done the other time he had filled in on another crew. He had also met me when I substituted. I saw the 448th formation approach and circle the field and then watched as one plane after another landed and parked, but none pulled into Binks's hardstand. I waited for an hour in hopes that the plane would show up, then began the walk back to our hut. I was very concerned but maintained hope that the plane, for some reason, had parked at another hardstand or perhaps had made an emergency landing at another base, as sometimes happened.

When I returned to the hut, no news was available. The word came a little later: Shorty's plane had ditched in the North Sea and only two of the crew had been picked up by the Air-Sea Rescue. Shorty was not one of them. I was shocked. Not wanting to cry in front of the other men, even though I knew they would understand, I went outside, where it was now dark, went for a walk, and let the tears come. I might as well have remained inside, for when I returned and glanced at the shelf above his cot where the photo of Mary, his fiancee, stood, the tears came again. Several of the men came and sat around me, not saying much, but letting me know that they sympathized.

The two men who were picked up, Sgt. Hood and Sgt. Nugent (I no longer remember their first names) came by our hut after being released from the hospital a few days later and told me what happened. With fuel tanks punctured by flak, they had insufficient gas to make England. As Lt. Binks attempted to ditch, a large wave caught the nose of the plane, which broke in half at the bomb bays. The back half, where Shorty was, sank immediately. Binks, Hood, and Nugent escaped from the front half. The latter two saw Binks struggling in the water not far away, but he went under before they could reach him. Hood and Nugent were picked up by Air-Sea Rescue. Neither flew again, and they were returned to the U.S.

-“Three Years in the Army Air Forces” by Dale R. VanBlair

Lt. Arthur Charles Delclisur

Arthur and Al Locke had become good friends during their months of serving together. Al mentions him in several of his letters to his wife, Patsy. Arthur died from injuries he sustained during the ditching of their plane on the mission to Berlin on April 29, 1944.Al wrote to Patsy in July 8, 1944 and said:

"I feel so bad at times I could just cry, almost. I felt so bad when Delclisur got killed and I went back to base and was the only one there that I did just sit down on the edge of my bed and cry. I'm not ashamed of it, things just happened so hard and fast. Although I believe that God was on my side or I wouldn't be on my way home to your arms again."

After Dale VanBlair recevied credit for shooting down a German Focke Wulf 190 on the Feb 21, 1944 mission to Munster, Germany, Arthur wrote this letter to Dale's parents.

Dear Mr, and Mrs. VanBlair:

You probably don't know who I am but the important thing is that I know who your son is and am proud to say it. I am proud to say I am a member of his crew and without him the crew would be weakened immeasurably. In the United States we know Dale wa s fine man to have on the crew but he hadn't shown himself and his capabilities until we got in combat. His calmness and balancing effect on the whole crew is a great help on all our missions. He has probably written you about getting the air medal, the other crew members with him, and the citation that goes with it could probably express my, and the rest of the crew's feelings about him better than I can. He will probably send it home to you and when you read the citation, you will see what I mean. I've been meaning to write you for a while, but what climaxed it was the day Dale got his first enemy fighter. The fighters were pretty heavy that day and he dealt with them with complete coolness and skill. The skill was obvious as he got one. All his "pals" on and off the crew were happy to hear the news and he was congratulated by all. All who know him like him, and we are proud to fly with men of his high calibur.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur C. Delclisur

P.S. I'm the bombardier on Dale's crew. The above letter is, in itself, a tribute to the kind of person Arthur Delclisur was: a very considerate, kind young man, one who was concerned about others. Not many would have taken the time to write such a letter. I thought highly of him, and had it not been for military protocol that kept officers and enlisted men from associating with each other socially, I am quite sure that we would have been close friends. He was, moreover, a top-notch bombardier and was one of the reasons we were selected to became a PFF lead crew.

` Dale VanBlair geovisit();

"I feel so bad at times I could just cry, almost. I felt so bad when Delclisur got killed and I went back to base and was the only one there that I did just sit down on the edge of my bed and cry. I'm not ashamed of it, things just happened so hard and fast. Although I believe that God was on my side or I wouldn't be on my way home to your arms again."

After Dale VanBlair recevied credit for shooting down a German Focke Wulf 190 on the Feb 21, 1944 mission to Munster, Germany, Arthur wrote this letter to Dale's parents.

Dear Mr, and Mrs. VanBlair:

You probably don't know who I am but the important thing is that I know who your son is and am proud to say it. I am proud to say I am a member of his crew and without him the crew would be weakened immeasurably. In the United States we know Dale wa s fine man to have on the crew but he hadn't shown himself and his capabilities until we got in combat. His calmness and balancing effect on the whole crew is a great help on all our missions. He has probably written you about getting the air medal, the other crew members with him, and the citation that goes with it could probably express my, and the rest of the crew's feelings about him better than I can. He will probably send it home to you and when you read the citation, you will see what I mean. I've been meaning to write you for a while, but what climaxed it was the day Dale got his first enemy fighter. The fighters were pretty heavy that day and he dealt with them with complete coolness and skill. The skill was obvious as he got one. All his "pals" on and off the crew were happy to hear the news and he was congratulated by all. All who know him like him, and we are proud to fly with men of his high calibur.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur C. Delclisur

P.S. I'm the bombardier on Dale's crew. The above letter is, in itself, a tribute to the kind of person Arthur Delclisur was: a very considerate, kind young man, one who was concerned about others. Not many would have taken the time to write such a letter. I thought highly of him, and had it not been for military protocol that kept officers and enlisted men from associating with each other socially, I am quite sure that we would have been close friends. He was, moreover, a top-notch bombardier and was one of the reasons we were selected to became a PFF lead crew.

` Dale VanBlair geovisit();

Lt. Kenneth O. Reed

This picture of Ken was taken on his 23rd birthday May 21, 1943 while he was home on leave.

Ken Reed died April 29, 1944 during the ditching. Lt. Reed was seen by Lt. Hortenstine with his head hanging into the water. John tried to hold onto him but became exhausted. Kenneth slipped away from him and was not seen again.

-"Three Years in the Army Air Force", by Dale R. VanBlair

I began corresponding with Mrs. Henrietta Reed, Ken Reed’s mother, following my return to the U.S, in November, 1944, and continued to do so until she was taken by cancer about twenty years later. The first excerpt, however, is from a letter that she wrote to our co-pilot, Errol Self, a copy of which I have. The second is from a letter that she wrote to me on March 1, 1945. These excerpts are a tribute not only to Ken but also to the spirit of American mothers like Mrs. Reed.—Dale R. VanBlair

“I am glad that Ken was brave and good and kind. He was always that way when he was with us—quiet and patient. Even as a child, he had dignity and courage. He was a good boy. Both his life and his death were good. I shall never forget him, dear Errol. He is with me even more than before he went away. Yes, Ken will be with you too when you need him, whether you fly again or not. You must not feel bad about Ken and the others who have gone away. God took them and left the rest of you. It was in His hands. Those of you who still have the gift of life on this dear earth will live lives that will be the fulfillment of our mighty struggle.

Someday we will understand the entire scheme of things when the Great Adventure comes to us, too. And I know that will mean happiness for you and all the fine boys who have gone ahead.”“And as for Ken, I understand that both John Hortenstine and Errol Self tried to keep him up. This knowledge is of superlative comfort to us. It was just one of those things, Dale. And we are so very grateful that seven of that splendid twelve are still here. We have looked the facts in the face from the beginning. I firmly believe that the five are all right. Why wouldn’t they be, Dale? They were fine fellows, and they with all of you that day, were doing their duty, a duty of great difficulty and a duty essential to the welfare of our fine country.”

Ken Reed died April 29, 1944 during the ditching. Lt. Reed was seen by Lt. Hortenstine with his head hanging into the water. John tried to hold onto him but became exhausted. Kenneth slipped away from him and was not seen again.

-"Three Years in the Army Air Force", by Dale R. VanBlair

I began corresponding with Mrs. Henrietta Reed, Ken Reed’s mother, following my return to the U.S, in November, 1944, and continued to do so until she was taken by cancer about twenty years later. The first excerpt, however, is from a letter that she wrote to our co-pilot, Errol Self, a copy of which I have. The second is from a letter that she wrote to me on March 1, 1945. These excerpts are a tribute not only to Ken but also to the spirit of American mothers like Mrs. Reed.—Dale R. VanBlair

“I am glad that Ken was brave and good and kind. He was always that way when he was with us—quiet and patient. Even as a child, he had dignity and courage. He was a good boy. Both his life and his death were good. I shall never forget him, dear Errol. He is with me even more than before he went away. Yes, Ken will be with you too when you need him, whether you fly again or not. You must not feel bad about Ken and the others who have gone away. God took them and left the rest of you. It was in His hands. Those of you who still have the gift of life on this dear earth will live lives that will be the fulfillment of our mighty struggle.

Someday we will understand the entire scheme of things when the Great Adventure comes to us, too. And I know that will mean happiness for you and all the fine boys who have gone ahead.”“And as for Ken, I understand that both John Hortenstine and Errol Self tried to keep him up. This knowledge is of superlative comfort to us. It was just one of those things, Dale. And we are so very grateful that seven of that splendid twelve are still here. We have looked the facts in the face from the beginning. I firmly believe that the five are all right. Why wouldn’t they be, Dale? They were fine fellows, and they with all of you that day, were doing their duty, a duty of great difficulty and a duty essential to the welfare of our fine country.”