Dale's Account of the mission and ditching on April 29, 1944

On the morning of April 29, 1944, we were briefed for a mission to Berlin as deputy lead for the 466th Group leading the 2nd Combat Wing, our fifth mission as a PFF lead crew with the 564th Squadron, 389th B.G. Not counting the mission of April 18, when we flew over the outskirts of Berlin, it would be my third time over the heart of the city, the first for the rest of the crew (I had filled in for injured members of other crews on the Berlin missions of March 6 and 9 while our officers were taking PFF training). Our target was the Friedrichstrasse rail station in the middle of Berlin, the center of the main rail and underground system networks.

On arriving at the hardstand where our plane was parked, I was introduced to Lt. John Bloznelis, who had been added to our crew as dead reckoning navigator. Lt. John Hortenstine, who had been with our crew from the beginning and was an excellent navigator, was the Mickey (radar) navigator. Lt. Harold Reed, who had been added to our crew on our second mission as a PFF lead crew on April 8, would be the instrument navigator. Because we had lost our regular engineer to bronchitis and because Cappy had said he was sick when he was awakened, we had two substitutes: Sgt. Harold Freeman as engineer and Sgt. Richard Wallace as radio operator. Also flying with us was Capt. Ralph Bryant, operations officer for the 786th Squadron of the 466th.

This was my eighteenth mission but only the thirteenth mission for the other six members of our original crew, and as we stood around on the hardstand awaiting taxi time, I joked with them about my having to sweat out two "unlucky thirteenth" missions: mine on March 16 and theirs. I should have known better.

The mission began ominously, for shortly after we became airborne, our plane developed generator problems. Normally we would have returned to our base; but since the lead plane had aborted because of mechanical, we had no choice but to take over the lead, with Captain Bryant now becoming Command Pilot.

After getting the formation assembled, we crossed the North Sea and Holland. Shortly before we entered Germany, our formation was attacked by several FW190s that were quickly driven off by our fighter escort. About twenty minutes later we were again hit by 190s, but again our escort of P51s quickly discouraged them, destroying at least one that I saw go down.

As we approached Berlin, Lt. Delclisur reported that not enough power was being generated to operate the bombsight properly and that we would have to bomb by radar, even though there was no undercast to interfere with the more accurate visual bombing. Immediately upon entering our bomb run we ran into intense flak. One shell scored a direct hit but, fortunately, was a dud. Instead of exploding on contact, it took our #3 engine and exited through the top of the wing, leaving a gaping hole. In the few minutes we were over Berlin our plane was hit several times. Not only had we lost an engine, but also it was leaking gasoline. Then, just after Lt. Delclisur released the flare that signaled the other planes to drop their bombs, our generators went completely out, leaving us with no power for gun turrets, radio, interphone, and other electrical equipment.

Not long after turning away from the target we were again attacked by a group of FW190s and a few 109s: our #2 engine was hit, and though it continued to run it was not putting out full power. Since we were caught without fighter support, the Germans were free to give us their undivided attention. Frequently they did not break off their attacks until they were on top of us. One flew by so close to me going from front to rear that I thought I might recognize the pilot if we ever met again. The loss of interphone and my limited view from my tail turret kept me ignorant of the engine problems and leaking gas tank; however, I knew we must have problems besides the loss of electrical power when I saw that we had dropped back to the rear of the formation.

The loss of power for turrets was a major concern to me. After going through the simple procedure for converting to hand cranks and foot firing pedals, I quickly learned that the emergency system was far from adequate. Using the hand cranks, I could not turn the turret and raise or lower the pair of fifties nearly fast enough to track any German plane that came into my view. The German that had attacked from the front and flown by so close to me had zoomed out of range long before I could do anything. Had my turret been operating normally, I'd have had a good chance of downing him. Fortunately, none of the enemy made a direct attack on our plane from the tail except for one FW190 that started my direction but swerved when I fired. I triggered a burst occasionally, primarily in the hope that the Germans would think my turret was functioning properly and stay clear. The front and top turret gunners were also operating their turrets manually and doing their best to fend off the Germans.

I watched Nazi fighters gang up on and down four Liberators that had been hit and were unable to keep up with the formation. That's us if we can not stay with the group, I thought, and kept an eye on the nearest Lib to see if we were dropping behind. A few minutes later I was relieved to note that we had maintained our position.

Some time later, however—I know not how long—we began to lag behind the formation, and two German fighters attacked from the front, puncturing a gas tank and knocking out another engine before a few P-47s picked us up and drove the enemy fighters off.

According to the mission analysis written on May 2, 1944, at 2nd Air Division Headquarters, a copy of which I obtained in 1989, the attack that began not long after we left Berlin lasted for as much an hour (seemed longer to me!) and cost the Division at least thirteen bombers, plus an additional six lost either to fighters or flak. Six were lost on the way in to the target.

When I at last saw the North Sea below us, I began to relax, for we had never been attacked after leaving the continent behind us. We had it made now. A few minutes later, however, I felt a tap on my back. It was Hank. "We're going to ditch," he shouted above the noise of the wind and the engines. "We don't have enough gas to get back."

After Hank brought me the bad news, I went back to the waist section to help throw all removable equipment out the waist windows. With no power for the radio, we could send no SOS; however, firing up flares calling for fighter support brought two P47s to us. Using hand signals, we tried to convey that we had to ditch and that our radio was out. They signaled that they understood and flew with us until the time came to hit the water.

As we assumed our ditching positions and then waited out the last few minutes before Lt. Locke set the plane down, I prayed that we might get through the ditching safely and be rescued. In view of the small place that I had given God in my life since entering service, I knew that I had no right to expect Him to answer my prayer; nevertheless, I prayed. I was aware that the Liberator was a difficult plane to ditch successfully and the rate of survival for crewmembers was rather low (I later learned that it ran only about one out of four). My closest friend, our crew's ball turret gunner, had been lost in a ditching when drafted to fill in on another crew on March 8. Only two of the crew were picked up. However, though I was quite concerned, I believed I would survive. I was still an optimist.

When Lt. Locke dragged the tail of the plane in the water to slow it prior to setting the plane down, the escape hatch flew open and icy water sprayed us. It was unbelievably cold. Someone--I no longer remember who--jumped up from where we were sitting on the floor between the two waist windows (a rather foolish move, I thought) and tried unsuccessfully to slam the hatch shut with his foot, then sat down again. Seconds later when Lt. Locke attempted to set the plane down, a large wave caught the nose. It was like slamming into a concrete wall. The plane broke behind the rear bomb bay, and I found myself instantaneously submerged in the frigid water without even having time to take a deep breath.

As I fought to get back to the surface, my forehead slammed against a metal object. My lungs were bursting, and I thought, I'm going to drown--what is it going to feel like? I even remembered reading somewhere that drowning was not such an unpleasant way to die and hoped it was true. I could not hold my breath one more second, yet somehow I did. Then my head broke above the surface, and I gratefully gulped in air. It was almost like being brought back from the dead--one moment after I had faced an imminent death, life was handed back to me.

I was still inside the waist section, which had not broken completely free of the forward section. If it had, I would have gone down with it. Seeing that the right waist window was completely blocked, I turned to the other window, but Pete was struggling to get through the half of it that was not covered by wreckage. For a few seconds I tried to force my way through a narrow gap in the tangle of aluminum, then dropped back into the water. I thought about pulling the compressed air cylinder cords to inflate my Mae West, but stopped on thinking that I might have to dive beneath the surface in order to get out. In retrospect, I am surprised that I could swim with all the clothes I had on, which included heavy flight boots, but I do not recall having any problem. Fearing the waist section would break loose any second and sink, I frantically looked for a way out. Spotting a small opening in the side of the fuselage at the water's surface, I paddled over to it. I was relieved to find the fuselage completely ripped away beneath the water with plenty of room for me to swim through.

As I was about to exit through the opening, someone screamed, "Help!" I turned around but could see no one. The last thing I wanted to do was to spend any more time inside the battered plane, but I could not leave if someone needed help. Hoping that the battered waist section would not break loose, I swam back a few feet. Still not finding anyone and not hearing another call for help, I swam back to the opening, pulled myself through, inflated my Mae West and began paddling away from the wreckage. I feared that if the plane sank, the suction would pull me under with it, but it continued to float.

Hoping that someone had released a life raft, I looked around. No raft. I thought about attempting to climb up onto the wing to pull the raft release handle but was afraid the plane would sink and take me with it. I spotted four men in the water, but the only one close to me was Lt. Delclisur, who had a large gash over one eye with blood streaming from it. He called, "Let's stay together." I tried to swim to him but could make no progress against the large waves, and my arms soon felt like lead and I gave up. The waves washed me further away from him, and I lost sight of everyone. Surprisingly, the plane was still floating, and I regretfully thought that I would have had ample time after exiting the waist section to swim to the wing, climb up on it, and release the life raft. I did not see our plane sink, so do not know how long it remained afloat.

I continued to paddle around dog fashion on top of my Mae West, finding it more and more difficult to hold my head up out of the water. I was now completely exhausted, but feared that if I turned over onto my back, the waves would wash over my head. Finally I could hold my head up no longer, rolled over and gratefully discovered that the Mae West held my head above the water and rode up over each wave with no effort on my part. Someone should have told us about that during our training, I thought. Having had no experience with life preservers, I didn't know that they were designed to float a person on his back.

Hearing the sound of an aircraft, I looked around and saw a B-24 approaching. It flew over very low with its bomb bay doors open, and I saw a man standing on the catwalk. I thought he was going to drop a life raft; however, the plane circled twice and flew off. Why didn't they do something, I wondered. I was angry.

I debated whether to take off the heavy flying boots that weighted down my feet, but since the Mae West was supporting me satisfactorily, decided against removing them. If the B24 should return and drop a raft, the boots might help retain some warmth in my feet even though they were wet.

I kept watching the horizon for a rescue boat, but none appeared. I had never felt so completely alone. Since my watch had stopped when we ditched, I had no idea how long I had been in the water, but it seemed like hours. One thing I was sure of. I was very, very cold, and I knew my chances of surviving were not good. I didn't give up and I didn't panic, but I kept thinking that I didn't want to die out here where my body might not ever be found.

Then, off in the distance, I saw the most beautiful object that I had ever laid eyes on in my 22+ years: a boat heading in my direction. I later learned that Royal Marine Launch 498 had been contacted by the P-47s and given our position. As it came closer, I waved and saw someone wave back. After watching the boat pick up two of our crew, I neither saw nor felt anything except for having, at one point, a vague sensation of someone trying to pour something down my throat.

Regaining consciousness was a strange experience. I was lying in a large, black tunnel. Remembering the ditching experience, I began to wonder if I were alive or dead, for there was no recollection of having been picked up. If I am dead, I thought, I must not be in Hell because I do not feel either hot or tortured, but I was afraid to open my eyes. When I finally did, I found myself lying in a bunk with Lt. Locke looking at me from the bunk above. I was alive and I was safe! What a flood of relief I felt.

He told me he was all right and that we were docked at Yarmouth and would soon be taken to a hospital. I had been unconscious for however long it had taken the boat to cover the thirty miles from our ditching site to Yarmouth. I had been in the water for from forty-five minutes to an hour and was the last of our crew to be picked up. My memory of someone trying to pour something down my throat was the result of their trying to get me to drink some scotch after picking me up. Since twenty minutes was about as long as a person was supposed to survive in the cold water, I was fortunate to be alive.

Lt. Locke filled me in on what had happened to the others as we waited to be taken to the hospital. Capt. Bryant and Lt. Delclisur died of injuries and shock after being picked up. Lt. Reed was seen by Lt. Hortenstine with his head hanging into the water. John tried to hold onto him but became exhausted. Kenneth slipped away from him and was not seen again. Lt. Bloznelis and Sgt. Freeman were never sighted, hence probably were killed in the ditching. What made Harold Freeman's death especially tragic was that he had completed his missions and was awaiting orders to return to the States when he was assigned to fill in on our crew. He had almost certainly written his parents about completing his tour, so that the word of his death would come as an even greater shock than if they thought he was still under the required number. A few weeks later, Mother wrote me that Harold's parents, who lived about thirty miles away in Hannibal, Missouri, had contacted her to see if she had additional information.

Lt. Self suffered a broken back and chipped shoulder bone. He later received the Soldier's Medal for freeing Pete, who had got caught on wreckage while trying to get through the waist window. It was probably Pete whom I had heard calling for help. Lt. Self had come up outside the waist window and, in spite of his injury, immediately pulled Pete loose after the one call for help. I have never figured out, however, why I did not see them when I exited through the opening in the fuselage, which was only a few feet behind the waist window. Perhaps I remained inside longer than I realized after hearing the call for help, thus giving them time to swim away.

The other survivors had escaped uninjured or with relatively minor injuries. Lt. Hortenstine, who had been in the compartment behind the cockpit for the ditching, had covered himself with flak jackets, which had prevented his being injured when the top turret broke loose and fell on him. He was able to push the turret off and escape through the top hatch. Hank came up outside of the waist section on the opposite side from which I escaped.

Lt. Locke was knocked out by the force of the impact. When he came to, he was under the water and still strapped to his seat. After releasing himself, he escaped through a hole in the side of the cockpit and pulled the cords to inflate his Mae West, only to find that the jacket was split and would not hold air. Fortunately, an oxygen bottle floated by, which he grabbed and held on to until being picked up.

Like Harold Freeman, Dick Wallace had also completed his missions and was awaiting return to the States when summoned to fly with us as radio operator. Dick, however, escaped with no injuries.

From RML 498 we were taken to a WREN hospital in Great Yarmouth.WRENs were British women serving in the navy. The one bright spot in the whole miserable experience was being taken care of by young, pretty nurses who gave us lots of attention. The thought occurred to me that Yarmouth might be a good place to spend a two-day pass, but I found out later that it was off limits to American military personnel.

Although I was not told so, I assume I was suffering from hypothermia,for I shivered and shivered and shivered. The nurses put hot water bottles around me and piled blankets on me, but I continued to shake. It was nearly dawn before I finally warmed up.

About the middle of the morning a nurse came in to tell us that our transportation to the 389th base had arrived. We had to remove the pajamas that the WREN hospital had provided and wrap ourselves in blankets brought from our base for the trip back to Hethel. We were stark naked beneath our blankets. We thought the English could at least have loaned us the pajamas for the trip home with the understanding they would be returned, but apparently their regulations forbade that. Such is the nature of red tape. The clothing we were wearing when picked up should have had time to dry, but we never saw it again. Perhaps it was returned to our supply, however.

I expected to see an ambulance waiting for us outside the hospital, but instead there sat a truck, of all things. Lt. Self was the only one transported in an ambulance. That was the longest thirty-mile ride I have ever taken. I was so weak that even sitting up in that rough-riding truck was almost more than I could manage; I was ready to collapse by the time we arrived at Hethel.

I suffered a skull fracture from the blow to the head and, three weeks later, developed spinal meningitis as a result of the time spent in the cold water. Thanks to penicillin, I recovered from the meningitis with no ill effects except for the complete loss of hearing in my right ear. When I walked into the CO's office to report after recovering from the meningitis, he looked up and said, "Don't tell the flight surgeon I told you this, but he told me not to expect you back."

That ended my flying. I spent the next six months as squadron gunnery sergeant before being returned to the States in October, 1944.

Lt. Locke later received the Distinguished Flying Cross for keeping the plane up in the formation with one engine out and another one damaged and bringing it back as far as he did. As he said to me, "Even if we had got back, those two engines would never have been used again!" Some may question its being possible for our plane to keep up. I see it as simply a tribute to the B-24's Pratt and Whitney engines and Lt. Locke's skill as a pilot.

One final footnote: had it not been for Capt. Bryant we might have made it back to Hethel. After we lost Virgil, our engineer, from our crew, Cappy had been assigned the responsibility of seeing that we used up the gas in the wing-tip tanks first when starting on a mission and then flipping the switch to the main tanks. With Cappy missing, the routine was upset, and Harold Freeman, our replacement engineer for the mission, forgot to use the auxiliary wing-tip tanks first before switching to the main tanks until we were out over the North Sea headed for the continent. At that time Harold started to get out of his top turret position to switch to those tanks, but Capt. Bryant ordered him back to the turret to watch for fighters. It would only have taken Harold a few seconds to switch to the wing-tip tanks and then, when that gas was about used up, another few seconds to switch back to the main tanks. No fighters could have sneaked up on us in that length of time; besides, the waist gunners could see almost all the sky covered by the top turret. Following the loss of our generators, no power was available to switch to the wing-tip tanks when we ran low on gas. Had Capt. Bryant not interfered, we would probably have had enough gas left in the main tanks to get us back to England. As Command Pilot, Bryant was commander of the formation, but not of our plane, which was Lt. Locke's responsibility. Bryant had no business interfering with Harold.

On arriving at the hardstand where our plane was parked, I was introduced to Lt. John Bloznelis, who had been added to our crew as dead reckoning navigator. Lt. John Hortenstine, who had been with our crew from the beginning and was an excellent navigator, was the Mickey (radar) navigator. Lt. Harold Reed, who had been added to our crew on our second mission as a PFF lead crew on April 8, would be the instrument navigator. Because we had lost our regular engineer to bronchitis and because Cappy had said he was sick when he was awakened, we had two substitutes: Sgt. Harold Freeman as engineer and Sgt. Richard Wallace as radio operator. Also flying with us was Capt. Ralph Bryant, operations officer for the 786th Squadron of the 466th.

This was my eighteenth mission but only the thirteenth mission for the other six members of our original crew, and as we stood around on the hardstand awaiting taxi time, I joked with them about my having to sweat out two "unlucky thirteenth" missions: mine on March 16 and theirs. I should have known better.

The mission began ominously, for shortly after we became airborne, our plane developed generator problems. Normally we would have returned to our base; but since the lead plane had aborted because of mechanical, we had no choice but to take over the lead, with Captain Bryant now becoming Command Pilot.

After getting the formation assembled, we crossed the North Sea and Holland. Shortly before we entered Germany, our formation was attacked by several FW190s that were quickly driven off by our fighter escort. About twenty minutes later we were again hit by 190s, but again our escort of P51s quickly discouraged them, destroying at least one that I saw go down.

As we approached Berlin, Lt. Delclisur reported that not enough power was being generated to operate the bombsight properly and that we would have to bomb by radar, even though there was no undercast to interfere with the more accurate visual bombing. Immediately upon entering our bomb run we ran into intense flak. One shell scored a direct hit but, fortunately, was a dud. Instead of exploding on contact, it took our #3 engine and exited through the top of the wing, leaving a gaping hole. In the few minutes we were over Berlin our plane was hit several times. Not only had we lost an engine, but also it was leaking gasoline. Then, just after Lt. Delclisur released the flare that signaled the other planes to drop their bombs, our generators went completely out, leaving us with no power for gun turrets, radio, interphone, and other electrical equipment.

Not long after turning away from the target we were again attacked by a group of FW190s and a few 109s: our #2 engine was hit, and though it continued to run it was not putting out full power. Since we were caught without fighter support, the Germans were free to give us their undivided attention. Frequently they did not break off their attacks until they were on top of us. One flew by so close to me going from front to rear that I thought I might recognize the pilot if we ever met again. The loss of interphone and my limited view from my tail turret kept me ignorant of the engine problems and leaking gas tank; however, I knew we must have problems besides the loss of electrical power when I saw that we had dropped back to the rear of the formation.

The loss of power for turrets was a major concern to me. After going through the simple procedure for converting to hand cranks and foot firing pedals, I quickly learned that the emergency system was far from adequate. Using the hand cranks, I could not turn the turret and raise or lower the pair of fifties nearly fast enough to track any German plane that came into my view. The German that had attacked from the front and flown by so close to me had zoomed out of range long before I could do anything. Had my turret been operating normally, I'd have had a good chance of downing him. Fortunately, none of the enemy made a direct attack on our plane from the tail except for one FW190 that started my direction but swerved when I fired. I triggered a burst occasionally, primarily in the hope that the Germans would think my turret was functioning properly and stay clear. The front and top turret gunners were also operating their turrets manually and doing their best to fend off the Germans.

I watched Nazi fighters gang up on and down four Liberators that had been hit and were unable to keep up with the formation. That's us if we can not stay with the group, I thought, and kept an eye on the nearest Lib to see if we were dropping behind. A few minutes later I was relieved to note that we had maintained our position.

Some time later, however—I know not how long—we began to lag behind the formation, and two German fighters attacked from the front, puncturing a gas tank and knocking out another engine before a few P-47s picked us up and drove the enemy fighters off.

According to the mission analysis written on May 2, 1944, at 2nd Air Division Headquarters, a copy of which I obtained in 1989, the attack that began not long after we left Berlin lasted for as much an hour (seemed longer to me!) and cost the Division at least thirteen bombers, plus an additional six lost either to fighters or flak. Six were lost on the way in to the target.

When I at last saw the North Sea below us, I began to relax, for we had never been attacked after leaving the continent behind us. We had it made now. A few minutes later, however, I felt a tap on my back. It was Hank. "We're going to ditch," he shouted above the noise of the wind and the engines. "We don't have enough gas to get back."

After Hank brought me the bad news, I went back to the waist section to help throw all removable equipment out the waist windows. With no power for the radio, we could send no SOS; however, firing up flares calling for fighter support brought two P47s to us. Using hand signals, we tried to convey that we had to ditch and that our radio was out. They signaled that they understood and flew with us until the time came to hit the water.

As we assumed our ditching positions and then waited out the last few minutes before Lt. Locke set the plane down, I prayed that we might get through the ditching safely and be rescued. In view of the small place that I had given God in my life since entering service, I knew that I had no right to expect Him to answer my prayer; nevertheless, I prayed. I was aware that the Liberator was a difficult plane to ditch successfully and the rate of survival for crewmembers was rather low (I later learned that it ran only about one out of four). My closest friend, our crew's ball turret gunner, had been lost in a ditching when drafted to fill in on another crew on March 8. Only two of the crew were picked up. However, though I was quite concerned, I believed I would survive. I was still an optimist.

When Lt. Locke dragged the tail of the plane in the water to slow it prior to setting the plane down, the escape hatch flew open and icy water sprayed us. It was unbelievably cold. Someone--I no longer remember who--jumped up from where we were sitting on the floor between the two waist windows (a rather foolish move, I thought) and tried unsuccessfully to slam the hatch shut with his foot, then sat down again. Seconds later when Lt. Locke attempted to set the plane down, a large wave caught the nose. It was like slamming into a concrete wall. The plane broke behind the rear bomb bay, and I found myself instantaneously submerged in the frigid water without even having time to take a deep breath.

As I fought to get back to the surface, my forehead slammed against a metal object. My lungs were bursting, and I thought, I'm going to drown--what is it going to feel like? I even remembered reading somewhere that drowning was not such an unpleasant way to die and hoped it was true. I could not hold my breath one more second, yet somehow I did. Then my head broke above the surface, and I gratefully gulped in air. It was almost like being brought back from the dead--one moment after I had faced an imminent death, life was handed back to me.

I was still inside the waist section, which had not broken completely free of the forward section. If it had, I would have gone down with it. Seeing that the right waist window was completely blocked, I turned to the other window, but Pete was struggling to get through the half of it that was not covered by wreckage. For a few seconds I tried to force my way through a narrow gap in the tangle of aluminum, then dropped back into the water. I thought about pulling the compressed air cylinder cords to inflate my Mae West, but stopped on thinking that I might have to dive beneath the surface in order to get out. In retrospect, I am surprised that I could swim with all the clothes I had on, which included heavy flight boots, but I do not recall having any problem. Fearing the waist section would break loose any second and sink, I frantically looked for a way out. Spotting a small opening in the side of the fuselage at the water's surface, I paddled over to it. I was relieved to find the fuselage completely ripped away beneath the water with plenty of room for me to swim through.

As I was about to exit through the opening, someone screamed, "Help!" I turned around but could see no one. The last thing I wanted to do was to spend any more time inside the battered plane, but I could not leave if someone needed help. Hoping that the battered waist section would not break loose, I swam back a few feet. Still not finding anyone and not hearing another call for help, I swam back to the opening, pulled myself through, inflated my Mae West and began paddling away from the wreckage. I feared that if the plane sank, the suction would pull me under with it, but it continued to float.

Hoping that someone had released a life raft, I looked around. No raft. I thought about attempting to climb up onto the wing to pull the raft release handle but was afraid the plane would sink and take me with it. I spotted four men in the water, but the only one close to me was Lt. Delclisur, who had a large gash over one eye with blood streaming from it. He called, "Let's stay together." I tried to swim to him but could make no progress against the large waves, and my arms soon felt like lead and I gave up. The waves washed me further away from him, and I lost sight of everyone. Surprisingly, the plane was still floating, and I regretfully thought that I would have had ample time after exiting the waist section to swim to the wing, climb up on it, and release the life raft. I did not see our plane sink, so do not know how long it remained afloat.

I continued to paddle around dog fashion on top of my Mae West, finding it more and more difficult to hold my head up out of the water. I was now completely exhausted, but feared that if I turned over onto my back, the waves would wash over my head. Finally I could hold my head up no longer, rolled over and gratefully discovered that the Mae West held my head above the water and rode up over each wave with no effort on my part. Someone should have told us about that during our training, I thought. Having had no experience with life preservers, I didn't know that they were designed to float a person on his back.

Hearing the sound of an aircraft, I looked around and saw a B-24 approaching. It flew over very low with its bomb bay doors open, and I saw a man standing on the catwalk. I thought he was going to drop a life raft; however, the plane circled twice and flew off. Why didn't they do something, I wondered. I was angry.

I debated whether to take off the heavy flying boots that weighted down my feet, but since the Mae West was supporting me satisfactorily, decided against removing them. If the B24 should return and drop a raft, the boots might help retain some warmth in my feet even though they were wet.

I kept watching the horizon for a rescue boat, but none appeared. I had never felt so completely alone. Since my watch had stopped when we ditched, I had no idea how long I had been in the water, but it seemed like hours. One thing I was sure of. I was very, very cold, and I knew my chances of surviving were not good. I didn't give up and I didn't panic, but I kept thinking that I didn't want to die out here where my body might not ever be found.

Then, off in the distance, I saw the most beautiful object that I had ever laid eyes on in my 22+ years: a boat heading in my direction. I later learned that Royal Marine Launch 498 had been contacted by the P-47s and given our position. As it came closer, I waved and saw someone wave back. After watching the boat pick up two of our crew, I neither saw nor felt anything except for having, at one point, a vague sensation of someone trying to pour something down my throat.

Regaining consciousness was a strange experience. I was lying in a large, black tunnel. Remembering the ditching experience, I began to wonder if I were alive or dead, for there was no recollection of having been picked up. If I am dead, I thought, I must not be in Hell because I do not feel either hot or tortured, but I was afraid to open my eyes. When I finally did, I found myself lying in a bunk with Lt. Locke looking at me from the bunk above. I was alive and I was safe! What a flood of relief I felt.

He told me he was all right and that we were docked at Yarmouth and would soon be taken to a hospital. I had been unconscious for however long it had taken the boat to cover the thirty miles from our ditching site to Yarmouth. I had been in the water for from forty-five minutes to an hour and was the last of our crew to be picked up. My memory of someone trying to pour something down my throat was the result of their trying to get me to drink some scotch after picking me up. Since twenty minutes was about as long as a person was supposed to survive in the cold water, I was fortunate to be alive.

Lt. Locke filled me in on what had happened to the others as we waited to be taken to the hospital. Capt. Bryant and Lt. Delclisur died of injuries and shock after being picked up. Lt. Reed was seen by Lt. Hortenstine with his head hanging into the water. John tried to hold onto him but became exhausted. Kenneth slipped away from him and was not seen again. Lt. Bloznelis and Sgt. Freeman were never sighted, hence probably were killed in the ditching. What made Harold Freeman's death especially tragic was that he had completed his missions and was awaiting orders to return to the States when he was assigned to fill in on our crew. He had almost certainly written his parents about completing his tour, so that the word of his death would come as an even greater shock than if they thought he was still under the required number. A few weeks later, Mother wrote me that Harold's parents, who lived about thirty miles away in Hannibal, Missouri, had contacted her to see if she had additional information.

Lt. Self suffered a broken back and chipped shoulder bone. He later received the Soldier's Medal for freeing Pete, who had got caught on wreckage while trying to get through the waist window. It was probably Pete whom I had heard calling for help. Lt. Self had come up outside the waist window and, in spite of his injury, immediately pulled Pete loose after the one call for help. I have never figured out, however, why I did not see them when I exited through the opening in the fuselage, which was only a few feet behind the waist window. Perhaps I remained inside longer than I realized after hearing the call for help, thus giving them time to swim away.

The other survivors had escaped uninjured or with relatively minor injuries. Lt. Hortenstine, who had been in the compartment behind the cockpit for the ditching, had covered himself with flak jackets, which had prevented his being injured when the top turret broke loose and fell on him. He was able to push the turret off and escape through the top hatch. Hank came up outside of the waist section on the opposite side from which I escaped.

Lt. Locke was knocked out by the force of the impact. When he came to, he was under the water and still strapped to his seat. After releasing himself, he escaped through a hole in the side of the cockpit and pulled the cords to inflate his Mae West, only to find that the jacket was split and would not hold air. Fortunately, an oxygen bottle floated by, which he grabbed and held on to until being picked up.

Like Harold Freeman, Dick Wallace had also completed his missions and was awaiting return to the States when summoned to fly with us as radio operator. Dick, however, escaped with no injuries.

From RML 498 we were taken to a WREN hospital in Great Yarmouth.WRENs were British women serving in the navy. The one bright spot in the whole miserable experience was being taken care of by young, pretty nurses who gave us lots of attention. The thought occurred to me that Yarmouth might be a good place to spend a two-day pass, but I found out later that it was off limits to American military personnel.

Although I was not told so, I assume I was suffering from hypothermia,for I shivered and shivered and shivered. The nurses put hot water bottles around me and piled blankets on me, but I continued to shake. It was nearly dawn before I finally warmed up.

About the middle of the morning a nurse came in to tell us that our transportation to the 389th base had arrived. We had to remove the pajamas that the WREN hospital had provided and wrap ourselves in blankets brought from our base for the trip back to Hethel. We were stark naked beneath our blankets. We thought the English could at least have loaned us the pajamas for the trip home with the understanding they would be returned, but apparently their regulations forbade that. Such is the nature of red tape. The clothing we were wearing when picked up should have had time to dry, but we never saw it again. Perhaps it was returned to our supply, however.

I expected to see an ambulance waiting for us outside the hospital, but instead there sat a truck, of all things. Lt. Self was the only one transported in an ambulance. That was the longest thirty-mile ride I have ever taken. I was so weak that even sitting up in that rough-riding truck was almost more than I could manage; I was ready to collapse by the time we arrived at Hethel.

I suffered a skull fracture from the blow to the head and, three weeks later, developed spinal meningitis as a result of the time spent in the cold water. Thanks to penicillin, I recovered from the meningitis with no ill effects except for the complete loss of hearing in my right ear. When I walked into the CO's office to report after recovering from the meningitis, he looked up and said, "Don't tell the flight surgeon I told you this, but he told me not to expect you back."

That ended my flying. I spent the next six months as squadron gunnery sergeant before being returned to the States in October, 1944.

Lt. Locke later received the Distinguished Flying Cross for keeping the plane up in the formation with one engine out and another one damaged and bringing it back as far as he did. As he said to me, "Even if we had got back, those two engines would never have been used again!" Some may question its being possible for our plane to keep up. I see it as simply a tribute to the B-24's Pratt and Whitney engines and Lt. Locke's skill as a pilot.

One final footnote: had it not been for Capt. Bryant we might have made it back to Hethel. After we lost Virgil, our engineer, from our crew, Cappy had been assigned the responsibility of seeing that we used up the gas in the wing-tip tanks first when starting on a mission and then flipping the switch to the main tanks. With Cappy missing, the routine was upset, and Harold Freeman, our replacement engineer for the mission, forgot to use the auxiliary wing-tip tanks first before switching to the main tanks until we were out over the North Sea headed for the continent. At that time Harold started to get out of his top turret position to switch to those tanks, but Capt. Bryant ordered him back to the turret to watch for fighters. It would only have taken Harold a few seconds to switch to the wing-tip tanks and then, when that gas was about used up, another few seconds to switch back to the main tanks. No fighters could have sneaked up on us in that length of time; besides, the waist gunners could see almost all the sky covered by the top turret. Following the loss of our generators, no power was available to switch to the wing-tip tanks when we ran low on gas. Had Capt. Bryant not interfered, we would probably have had enough gas left in the main tanks to get us back to England. As Command Pilot, Bryant was commander of the formation, but not of our plane, which was Lt. Locke's responsibility. Bryant had no business interfering with Harold.

Al Locke’s account of the April 29, 1944 mission to Berlin.

On the morning of April 29th we were assigned as deputy lead of the 466th group which was leading the 46th Combat wing on a mission to Berlin. As we taxied our on the runway for takeoff, Capt. England, assigned as lead ship, sent word that, due to a dangerous bomb release, they would take off late and join us in the air. We then took off, formed the wing, and formed the division, on course and on time. Shortly afterwards, the engineer Sgt. Freeman, reported that two generators were out. I asked him if the others were alright- he replied that they were, but that two generators wouldn’t last long with the extreme load of our equipment. The Command Pilot decided to keep the lead, since there were none others he thought able to replace us.

We continued on course as lead, since the other lead ship didn’t show up (I later found out they had further mechanical difficulty).

Since we were draining excessive current I turned off the automatic pilot and all other electric source we could get along without so as to give full current to our special equipment for navigation purposes, there being a 6/10 to 8/10 cloud cover at the time.

When we arrived at the mission IP I informed the Capt. That we would have to bomb by PFF, though the conditions bordered on visual, since a checkup showed we had not enough current to operate the bombsight. After entering the city, we obtained a direct hit on no. 3 engine by an 88mm shell which did not explode but tore through the wing leaving a gaping hole. This however didn’t interfere with the bomb run, as we got bombs away about 2 minutes later, on the center of the city.

On leaving Berlin I feathered number 3 engine and the interphone and electrical system failed soon after.

The captain suggested that we take a course for home, since we were off course to the south. But since we were with the division I suggested that we say with the other wings, fighter support being completely lacking and he agreed.

Coming back on course again fighters harassed us from the Magdeburg area to the Zuider Zee.

At two different times I saw about 30 nazi fighters “gang up” abreast and attack elements of our wing.

After progressing all the way across Germany, it became apparent that we were unable to lead the wing because of our slow airspeed and fluctuating power. It was a continual fight to keep the manifold pressure under control on two of the remaining three engines.

We left the combat wing lead and came up to the rear of the formation, and almost immediately our plane was attacked by enemy fighters, who were driven off by the gunners, operating their turrets manually. The attacks were repeated in about 15 minutes by other fighters, again without success.

We then picked up escort of two P-47s by firing flares since we were unable to keep up with the formation.

We continued on course as lead, since the other lead ship didn’t show up (I later found out they had further mechanical difficulty).

Since we were draining excessive current I turned off the automatic pilot and all other electric source we could get along without so as to give full current to our special equipment for navigation purposes, there being a 6/10 to 8/10 cloud cover at the time.

When we arrived at the mission IP I informed the Capt. That we would have to bomb by PFF, though the conditions bordered on visual, since a checkup showed we had not enough current to operate the bombsight. After entering the city, we obtained a direct hit on no. 3 engine by an 88mm shell which did not explode but tore through the wing leaving a gaping hole. This however didn’t interfere with the bomb run, as we got bombs away about 2 minutes later, on the center of the city.

On leaving Berlin I feathered number 3 engine and the interphone and electrical system failed soon after.

The captain suggested that we take a course for home, since we were off course to the south. But since we were with the division I suggested that we say with the other wings, fighter support being completely lacking and he agreed.

Coming back on course again fighters harassed us from the Magdeburg area to the Zuider Zee.

At two different times I saw about 30 nazi fighters “gang up” abreast and attack elements of our wing.

After progressing all the way across Germany, it became apparent that we were unable to lead the wing because of our slow airspeed and fluctuating power. It was a continual fight to keep the manifold pressure under control on two of the remaining three engines.

We left the combat wing lead and came up to the rear of the formation, and almost immediately our plane was attacked by enemy fighters, who were driven off by the gunners, operating their turrets manually. The attacks were repeated in about 15 minutes by other fighters, again without success.

We then picked up escort of two P-47s by firing flares since we were unable to keep up with the formation.

The Goldfish Club

This patch is the insignia of The Goldfish Club. Pilots and crewmembers who survive a plane ditching are eligible to join. Al Locke joined the club sometime after the ditching, but we are unsure of exactly when. It was originally an RAF/RCAF club, and was adopted by American aircrews although it was an unofficial insignia. Because it was unofficial, it was worn under the lapel, out of sight since you could be busted for "being out of uniform" for openly displaying it.

For more information on The Goldfish Club, visit our Goldfish Club page.

For more information on The Goldfish Club, visit our Goldfish Club page.

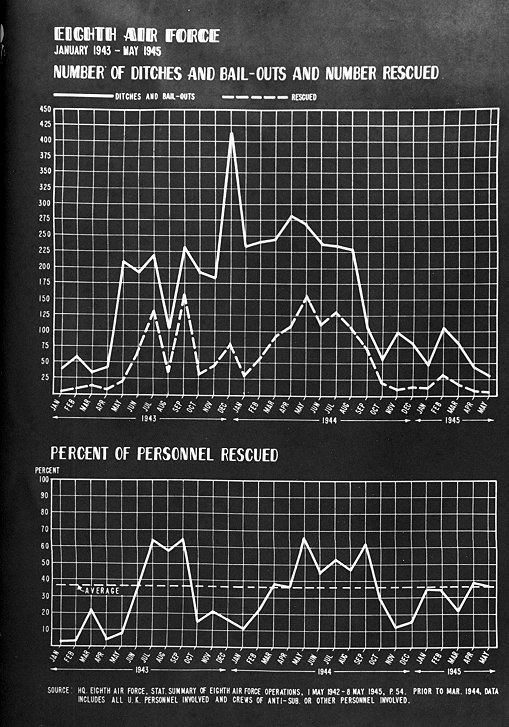

A graphical representation of the 8th Air Force ditching and rescue numbers for WWII.

From: US Air Force Historical Study No. 95 Air-sea rescue 1941-1952, USAF Historical Studies Institute Air University, Frank E. Ransom, 1954, pg 45a