Seething Airfield

Home of the 448thBG

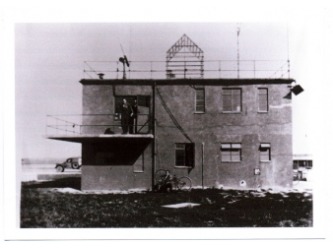

Dale acquired these pictures from the 448th BG museum now located in the control tower during a trip to England in 1986.

The first picture shows the Seething control tower during WWII, and the second and third pictures the enlisted crew quarters.

The first picture shows the Seething control tower during WWII, and the second and third pictures the enlisted crew quarters.

The next morning, December 11, we made the short flight to the 448th base near Seething, a very small village about seven miles from Norwich. Because of a low cloud cover, we flew only a few hundred feet above the countryside. I was surprised by how small the hedge-bordered fields were compared with those back home. I was getting a much better impression of England than I had formed the previous night. Even though it was December, various shades of green predominated, and I liked the neat, ordered appearance of the small fields.

As we sat around that evening talking to others in our hut, they told us about the welcome which the 448th had received from Germany. One of the men had bought a radio on his first trip into Norwich, and since German stations came in quite clearly and often played better popular music than most of the English stations, he had frequently tuned in to them. As the men were listening to a German station on the new radio, they heard the announcer say, “We welcome the 448th Bomb. Group to the E.T.O. [European Theater of Operations]. We hope you enjoy your stay here, and we look forward to meeting you.”

On December 22 the 448th made its first mission, but we were not alerted. Twenty-six crews took off for Osnabruck, Germany, a manufacturing center. Only thirteen made the mission; the others returned early because of not being able to get into formation as a result of bad weather and lack of experience. The thirteen making the mission were attacked at the German border by ME109s and FW190s, with a loss of three aircraft (thirty men) and five others heavily damaged. The returnees we had talked to in Puerto Rico had apparently not been exaggerating. Because of their inexperience, the pilots failed to maintain a close formation so that the gunners could direct a concentrated fire at the attacking fighters. To make matters worse, photographs of the target taken two days later showed no damage done. It was not an auspicious beginning, but it was a good day for us to have remained on the ground.

Seething was quite different from the American bases to which we were accustomed. To begin with, there were no rows of barracks--in fact, no barracks. Instead we were housed in Nissen huts, metal half-round structures. Because of the necessity of camouflage from German air attacks, the huts were not in neat rows, but rather were placed here and there--under trees, wherever possible. Instead of being heated by forced-air furnaces, each hut had a coke or charcoal stove about thirty inches high and eighteen in diameter, quite small for the space the stove had to heat. The charcoal had to be started with wood which, in turn, had to be stolen from somewhere. Immediately behind our hut was a wooded area from which we could usually scrounge enough dead limbs to start a fire. Since starting a decent one would take from thirty minutes to an hour, we tried not to let the fire go out at night in times when an ample supply of charcoal was available. Our crew was fortunate in that our area in the hut was not far from the stove

Although most of the men slept on double bunks, there were a few singles, and Shorty and I claimed two of these side by side. The advantage was that you did not get awakened by someone bouncing around above you, for the double bunks were not all that stable. We were issued six blankets, and it sometimes took all of them to stay warm. Since we had mattresses to stop the cold air from underneath, we could pile all our blankets on top of us. The mattresses, instead of being a single unit, consisted of three pads about two feet square placed inside a mattress cover and were commonly referred to as "biscuits." They were not too comfortable and tended to separate, thus leaving a gap of two or three inches. When I made up my bed that first night, I caused quite a stir on producing my two sheets. During my year in England, I knew no one else with sheets, for they were very scarce in the stores and the 8th Air Force did not furnish them.

Seething was a newly constructed field, and it showed. Mud was everywhere, including walks and roads. The difference between the walks and the unpaved areas was that the walks provided a firm bottom for the mud. We tracked mud into our huts, the mess hall, and every other building we entered. The one good thing I can say about Col. Thompson is that he did not order any quarters inspections during those first few weeks.

Showering and shaving was a rather sporadic affair. Central showers were available, but hot water usually was not. As I recall, we might have averaged hot water one day of every seven to ten, and then for only two or three hours before the supply ran cold (nothing like getting all soaped up and then having the hot water run out). Someone from our hut would come in with the news that the water was hot, and there would then be an exodus to the shower room. As for shaving, no one did it regularly. I probably averaged shaving every three days. Since hot water usually was not available and eliminating a three-day growth with cold water was--for me, at least--a painful

experience, I would fill my steel helmet with cold water and heat it by dipping a hot stove lid into it. Not liking to wear an oxygen mask for several hours over a beard stubble, I always shaved the evening before we were to fly a mission.

Inspections were a rarity. At Seething, however, because of the mud, we swept out the hut regularly and even mopped occasionally. After our crew's subsequent transfer to Hethel , the 389th base, in March, we found mud no longer a problem, since it was an older base than Seething; hence, mopping here was done far less often than at Seething. At Hethel we were permitted to shower on Tuesday and Saturday, but hot water was sometimes not available on those days.

Flying personnel had no assigned duties except to fly their missions. Because of the frequency with which bad weather during the winter caused canceled missions, plus the fact that not every crew flew every mission made by the group, we averaged only about a mission a week during the winter months. For example, my eighteen missions spanned seventeen weeks. That left a lot of free time. Poker was a popular pastime with most of the men (I did not participate for several months), and lots of letters were written. Since I wrote my parents at least every three days and frequently more often (I had written every day while in the States) and also corresponded with several other relatives and friends, letter writing occupied quite a bit of my time. We made trips to the Aeroclub, the enlisted men's club, where books and newspapers were available. Also, we were free to take the truck taxi into Norwich as frequently as we wished. Special passes were required only for overnight or longer leaves.

Movies were available during the evening at the base theater. Also, a U.S.O. group occasionally came around to entertain us. One of the best I remember seeing featured Jimmy Cagney, who did several of his numbers from "Yankee Doodle Dandy."

-"Three Years in the Army Air Forces" by Dale R. VanBlair, pg 20-22

As we sat around that evening talking to others in our hut, they told us about the welcome which the 448th had received from Germany. One of the men had bought a radio on his first trip into Norwich, and since German stations came in quite clearly and often played better popular music than most of the English stations, he had frequently tuned in to them. As the men were listening to a German station on the new radio, they heard the announcer say, “We welcome the 448th Bomb. Group to the E.T.O. [European Theater of Operations]. We hope you enjoy your stay here, and we look forward to meeting you.”

On December 22 the 448th made its first mission, but we were not alerted. Twenty-six crews took off for Osnabruck, Germany, a manufacturing center. Only thirteen made the mission; the others returned early because of not being able to get into formation as a result of bad weather and lack of experience. The thirteen making the mission were attacked at the German border by ME109s and FW190s, with a loss of three aircraft (thirty men) and five others heavily damaged. The returnees we had talked to in Puerto Rico had apparently not been exaggerating. Because of their inexperience, the pilots failed to maintain a close formation so that the gunners could direct a concentrated fire at the attacking fighters. To make matters worse, photographs of the target taken two days later showed no damage done. It was not an auspicious beginning, but it was a good day for us to have remained on the ground.

Seething was quite different from the American bases to which we were accustomed. To begin with, there were no rows of barracks--in fact, no barracks. Instead we were housed in Nissen huts, metal half-round structures. Because of the necessity of camouflage from German air attacks, the huts were not in neat rows, but rather were placed here and there--under trees, wherever possible. Instead of being heated by forced-air furnaces, each hut had a coke or charcoal stove about thirty inches high and eighteen in diameter, quite small for the space the stove had to heat. The charcoal had to be started with wood which, in turn, had to be stolen from somewhere. Immediately behind our hut was a wooded area from which we could usually scrounge enough dead limbs to start a fire. Since starting a decent one would take from thirty minutes to an hour, we tried not to let the fire go out at night in times when an ample supply of charcoal was available. Our crew was fortunate in that our area in the hut was not far from the stove

Although most of the men slept on double bunks, there were a few singles, and Shorty and I claimed two of these side by side. The advantage was that you did not get awakened by someone bouncing around above you, for the double bunks were not all that stable. We were issued six blankets, and it sometimes took all of them to stay warm. Since we had mattresses to stop the cold air from underneath, we could pile all our blankets on top of us. The mattresses, instead of being a single unit, consisted of three pads about two feet square placed inside a mattress cover and were commonly referred to as "biscuits." They were not too comfortable and tended to separate, thus leaving a gap of two or three inches. When I made up my bed that first night, I caused quite a stir on producing my two sheets. During my year in England, I knew no one else with sheets, for they were very scarce in the stores and the 8th Air Force did not furnish them.

Seething was a newly constructed field, and it showed. Mud was everywhere, including walks and roads. The difference between the walks and the unpaved areas was that the walks provided a firm bottom for the mud. We tracked mud into our huts, the mess hall, and every other building we entered. The one good thing I can say about Col. Thompson is that he did not order any quarters inspections during those first few weeks.

Showering and shaving was a rather sporadic affair. Central showers were available, but hot water usually was not. As I recall, we might have averaged hot water one day of every seven to ten, and then for only two or three hours before the supply ran cold (nothing like getting all soaped up and then having the hot water run out). Someone from our hut would come in with the news that the water was hot, and there would then be an exodus to the shower room. As for shaving, no one did it regularly. I probably averaged shaving every three days. Since hot water usually was not available and eliminating a three-day growth with cold water was--for me, at least--a painful

experience, I would fill my steel helmet with cold water and heat it by dipping a hot stove lid into it. Not liking to wear an oxygen mask for several hours over a beard stubble, I always shaved the evening before we were to fly a mission.

Inspections were a rarity. At Seething, however, because of the mud, we swept out the hut regularly and even mopped occasionally. After our crew's subsequent transfer to Hethel , the 389th base, in March, we found mud no longer a problem, since it was an older base than Seething; hence, mopping here was done far less often than at Seething. At Hethel we were permitted to shower on Tuesday and Saturday, but hot water was sometimes not available on those days.

Flying personnel had no assigned duties except to fly their missions. Because of the frequency with which bad weather during the winter caused canceled missions, plus the fact that not every crew flew every mission made by the group, we averaged only about a mission a week during the winter months. For example, my eighteen missions spanned seventeen weeks. That left a lot of free time. Poker was a popular pastime with most of the men (I did not participate for several months), and lots of letters were written. Since I wrote my parents at least every three days and frequently more often (I had written every day while in the States) and also corresponded with several other relatives and friends, letter writing occupied quite a bit of my time. We made trips to the Aeroclub, the enlisted men's club, where books and newspapers were available. Also, we were free to take the truck taxi into Norwich as frequently as we wished. Special passes were required only for overnight or longer leaves.

Movies were available during the evening at the base theater. Also, a U.S.O. group occasionally came around to entertain us. One of the best I remember seeing featured Jimmy Cagney, who did several of his numbers from "Yankee Doodle Dandy."

-"Three Years in the Army Air Forces" by Dale R. VanBlair, pg 20-22